England is a country in which certain aspects of linguistics have an unusually long history. Linguistic description becomes a matter of practical importance to a nation when it evolves a standard or ‘official’ language for itself out of the welter of diverse and conflicting local usages normally found in any territory that has been settled for a considerable time. England was already developing a recognized standard language by the eleventh century. Phonetic study in the modern sense was pioneered by Henry Sweet (1845-192). He was the greatest of the few historical linguists whom Britain produced in the nineteenth century to rival the burgeoning of historical linguistics in Germany. Sweet based his historical studies on a detailed understanding of the workings of the vocal organs.

Sweet’s phonetics was practical as well as academic; he was actively concerned with systematizing phonetic transcription in connection with problems of language-teaching and of spelling reform. Sweet’s general approach to phonetics was continued by Daniel Jones (1881-1967), who took the subject up as a hobby, suggested to the authorities of University College, London, that they ought to consider teaching the phonetics of French.

Daniel Jones stressed the importance for language study of thorough training in the practical skills of perceiving, transcribing, and reproducing minute distinctions of speech-sound. Thanks to the traditions established by Sweet and Jones, the ‘ear-training’ aspect of phonetics plays a large part in university courses in linguistics in Britain, and British linguistic research tends to be informed by meticulous attention to phonetic detail.

The man who turned linguistics proper into a recognized, distinct academic subject in Britain was J.R. Firth (1890-1960). In 1938 he moved to the linguistics department of the School of Oriental and African Studies, where in 1944 he became the first Professor of General Linguistics in Great Britain. Until quite recently, the majority of university teachers of linguistics in Britain were people who had trained under Firth’s aegis and whose work reflected his ideas, so that, although linguistics eventually began to flourish in a number of other locations, the name ‘London School’ is quite appropriate for the distinctively British approach to the subject.

London linguists were typically dealing with languages that had plenty of speakers and which faced the task of evolving into efficient vehicles of communication for modern civilization. It also meant that London linguists were prepared to spend their time on relatively abstruse theorizing based on limited areas of data. Firth’s own theorizing concerned mainly phonology and semantics.

Whether the potential contributions of the London School will succeed in finding a permanent place in the international pool of linguistic scholarship is another matter. London and other universities in Britain and the Commonwealth still contain scholars working within the Firthian tradition, but by now these are outnumbered, or at least outpublished, by a later, thoroughly Chomskyanized generation.

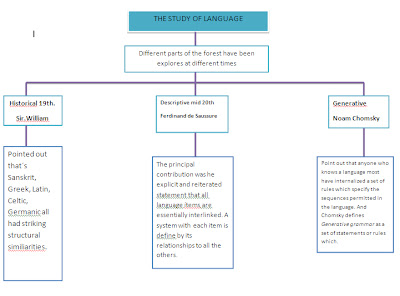

Linguistic theory can be defined as a framework that structures or guides the study of languages. Since its inception as a scientific discipline in the late 1800s and early 1900s, linguistic theory has evolved from Ferdinand de Saussure's theory of structuralism, to variations on Noam Chomsky's theory of transformational generative grammar

miércoles, 29 de febrero de 2012

lunes, 27 de febrero de 2012

lunes, 20 de febrero de 2012

Functional Linguistics: the Prague School

The Prague School practised a special style of synchronic Linguistics, and although most of the scholars whom one thinks of as members of the school worked in Prague or at least in Czechoslovakia, the term is used also to cover certain scholars elsewhere who consciously adhered to the Prague style.

For a linguist working in the American tradition, a grammar is a set of elements ‘emes’ of various kinds in Bloomfield´s framework, ‘rules’ of various sorts for a Chomskyan; the anakyst seems to take much the same attitude to the linguistic structure as one might take to a work of art, in that it does not usually occur to him to point to a particular element and ask ‘what´s that for?’- he is rather content to describe and to contemplate.

Prague linguists, on the other hand, looked at languages as one might look at a motor, seeking to understand what jobs the various components were doing an how the nature of one component determined the nature of others.

One fairly straightforward example of functional explanation in Mathesius´s own work concerns his use of terms commonly translated theme and rheme, and the notion which has come to be called ‘Functional Sentence Perspective’ by recent writers working in the Prague tradition.

According to Mathesius, the need for continuity means that a sentence will commonly fall into two parts: the theme, wich refers to something about which the hearer already knows, and the rheme, which states some new fact about that given topic. Unless certain special effects are animed at, theme will precede rheme, so that the peg may be established in the hearer´s mind before anything new has to be hung on it.

Even in English the passive has a second function: it enables us to reconcile the ocassional wish not to be explicit about the identity of the actor with the grammatical requirement that each finite verb have a subject, so that we can say Eve was kissed if were are unable or unwilling to say who kissed her.

It would be inaccurate to suggest that the notion of Functional Sentence Perspective was wholly unknown in American linguistics; some of the Descriptivists did use the terms ‘topic’ and ‘comment’ in much the same way as Mathesius´s ‘theme’ and ‘rheme’. A related point is that many Prague linguists were actively interesed in questions of standardizing linguistic usage.

The American Descriptivists not only, quite rightly, drew a logical distinction between linguistic description and linguistic prescription, but furthermore left their followers in little doubt that prescription was an improper, unprofessional activity in which no respectable linguist would indulge.

The theory of theme and rheme by no means exhausts Mathesius´s contributions to the functional view of grammar; given more space, I might have included a discussion of his notion of ‘functional onomatology’, which treats the coining of novel vocabulary items as a task which different languages solve in characteristically different ways.

Prince Nikolai Sergeyevich Trubetzkoy was one of the members of the ‘Prgue School’ not based in Czechoslovakia. He belonged to a scholarly family of the Russian nobility; his father had been a professor of philosophy and Rector of Moscow University. Trubetzkoy began at an early age to study Finno-Ugric and Caucasian folklore and philology; he was a student of Indo-European linguistics at his father´s university, and became a member of staff there in 1916.

Trubetzkoyan phonology, like that of the American Descriptivists, gives a central role to the phoneme; but Trubetzkoy, and the Prague School in general, were interested primarily in the paradigmatic relations between phonemes, i.e. the nature of the oppositions between the phonemes that potentially contrast with one another at a given point in a phonological structure, rather than in the syntagmate relations which determine how phonemes may be organized into sequences in a language.

Trubetzkoy, in the Principles, establishes a rather sophisticated system of phonological typology- that is, a language has, rather than simply treating its phonological structure in the take-it-or-leave-it American fashion as a set of isolated facts.

What is particularly relevant to our present discussion is that Trubetzkoy distinguished various functions that can be served by a phonological opposition. Consider the opposition between presence and absence of stress, for instance: there are perhaps rather few languages in which this is regularly distinctive.

In languages with more variable stress position, such as English or Russian, stress has less delimitative function and scarcely any distinctive function(pairs such as súbject (n) ~ subjéct (v), which are almost identical phonetically except for position of stress, are rare in English); but it has a culminative function: there is, very roughly speaking and ignoring a few ‘clitics’ such as a and the, one and only one main stress per word in English, so that perception of stress tells the hearer how many words he must segment the signal into, although it does not tell him where to make the cuts.

The Descriptivists thought of all phonological contrast as ‘distinctive’ contrast in Trubetzkoy´s sense. In the case of the fixed stress of Czech, for instance, a Descriptivist would have said either that it never keeps different words apart and is therefore to be ignored as non-phonemic, or else that there is a phonemic contrast between stress and its absence which is fully on a par, logically, with the opposition between /p/ and /b/ or /m/ and /n/. Trubetzkoy´s approach seems considerably more insightful than either of these alternatives.

A phonetic oppositon which fulfils the representation function will normally be a phonemic contrast; but distinctions between the allophones of a given phoneme, where the choice is not determined by the phonemic environment, will often play an expressive or conative role.

Another manofestation of the Prague attitude that language is a tool which has a job (or, rather, a wide variety of jobs) to do is the fact that members of that School were much preoccupied with the aesthetic, literaly aspects of language use (Gravin 1964 provides and anthology of some of this work).

If American linguists ignored (and still ignore) the aesthetic aspects of language, this is clearly because of their anxiety that linguistics should be a science. Bloomfieldians and Chomskyans disagree radically about the nature of science, but they are united in wainting to place linguistics firmly on the science side of the arts/science divide.

The first of these is what may be called the therapeutic theory of sound-change. Mathesius, and following him various other members of the Prague School, had the notion that sound changes were to be explained as the result of a striving towars a sort of ideal balance or resolution of various conflicting pressures; for instance, the need for a language too have a large variety of phonetic shapes available to keep its words distinct conflicts with the need for speech to be comprehensible despite inevitably inexact pronunciation, and at a more specific level the tendency in English, say, to pronounce the phoneme /e/ as a relatively close vowel in order to distinguish it clearly from /æ/ conflicts with the tendency to make it relatively open in order to distinguish in clearly from /I/.

The Prague School argues for system in diachrony too, and indeed it claims that linguistic change is determined by, as well as determining, synchronic état de langue.

The scholar who has done most to turn the therapeutic view of sound-change into an explicit, sophisticated theory is the Frenchman, André Martinet. The book in which Martinet set out his theories of diachronic phonology most fully is significantly entiled Économie des Changements Phonétiques.

One of the key concepts in Martinet´s account of sound-change is that of the functional yield of a phonological opposition. The functional yield of an opposition is, to put it simply, the amount of work it does in distinguishing utterances which are otherwise alike.

The history of Mandarin Chinese, for instance, has been one of repeated massive losses of phonological distinctions: final stops dropped, the voice contrast in initial consonants was lost, final m merged with n, the vowel system was greatly simplified,etc.

The language has of course compensated for his loss of phonological distinctions – if it had not, contemporary Mandarin would be so ambiguous as to be wholly unusuable.

Perhaps this obituary for Martinet´s theory of sound – change is premature; one can think of ways in which some sort of reaguard action might be mounted in its defence.

Sir Karl Popper has taught us that the first duty of a scientist is to ensure that his claims are potentially falsifiable, because statements about observable reality which could be overturned by no conceivable evidence are empty statements. Martinet´s defeat is therefore an honourable one.

Roman Osipovich Jakobson is a scholar of Russian origin; he took his first degree, in Oriental languages, at Moscow University. From the early 1920´s onwards he study and taught in Prague, and moved to a chair at the University of Bron in 1933, remaining there until the Nazi occupation forced him to leave. Jakobson was one of the founding members of the Prague Linguistics Circle.

Jakobson´s intellectual interests are broad and reflect those of the Prague School as a whole, he has written a great deal, for instance, on the structuralist approach to literature.

The essence of jakobson´s approach to phonology is the notion that there is a relatively simple, orderly, universal ‘psychological system’ of sounds underlying the chaotic wealth of different kinds of sound observed by the phonetician.

Speech-sounds may be characterized in terms of a number of distinct and independient or quasi-independient parameters, as we shall call them.

One of the lessons of articulatoty phonetics is that human vocal anatomy provides a very large range of different phonetic parameters – far more, probably, than any individual language uses distinctively.

The articulatory phonetician would be much more inclined to say that parameters which appear prima facie are really continuous rather than vice versa.

The Descriptivists emphasized that languages differ unpredictably in the particular phonetic parameters which they utilize distinctively, and in the number of values which they distinguish on parameters which are physycally continuous. The ideas just outlined are classically expressed in Jakobson, Fant and Halle´s Preliminaries to Speech Analysis.

The notion that the universal distinctive features are organized into an innate hierarchy of relative importance or priority appears in a book which Jakobson published in the period between leaving Czechoslovakia and arriving in America.

Jakobson uses observations of the latter categories as evidence against those who would suggest that his universals have relatively superficial physiological explanations.

The difficulty with this aspect of Jakobson´s work is that his evidence is highly anecdotal – he bases his ‘universals’ of synaesthesia on a tiny handful of reports about indicuduals; and one anecdote is always very vulnerable to a counter-anecdote.

One of the Characteristics of the Prague approach to language was a readiness to acknowledge that a given language might include a range of alternative ‘systems’, ‘registers’, or ‘styles’, where American Descriptivists tended to insist on treating a language as a single unitary system.

Age and social standing of the speaker, degree of formality of the interview, and other factors all interact to determine in a highly systematic and predictable fashion the proportion of possible post-vocalic rs which are actually pronounced in any given utterance.

Saussure stressed the social nature of language, and he insisted that linguistics as a social science must ignore historical data because, for the speaker, the history of his language does not exist – a point that seemed undeniable.

miércoles, 15 de febrero de 2012

The Study of Language

Sassure: Language as a social fact

Mongin- Ferdinand de Saussure

|

Emile Durkheim

|

Gabriel Tarde

|

Noam Chomsky

|

Hilary Putnam

| ||||||

Who defined thenotion of ‘synchronic linguistics’ the study of languages as systems existing at a given point in time, as opposed to the historical linguistics wich had seemed to his contemporaries the only possible approach to the subject.

Two of his colleagues

Historical linguistics is a relatively simple, even beguiling affair of describing one isolated event after another.

Synchronic description is a more serious and difficult ocupation, since here there can be not questions of presenting insolated anecdotes.

A language comprosed a set of “signs” each sign being the union of a signifian with a signs cannot be considered in insolation, since but theire pronunciation and there meaning are defined by their contrast with the other signs of the system.

Saussure`s assignment of syntax to parole rather than to langue is linked in another with the question of linguistic structure as social rather than psychological fact. Argued that langue must be a social fact on the grounds that no individual knows his mother-tongue completely.

|

Is the founder of sociology as a recognized empirical dicipline: to understand what Saussure means by calling lenguages “social facts”.

Propunded the notion of “social facts” in the Rules of Sociological Method, the task of sociology was to study and describe reaim of phonema quite distinct in kind both from the phonema of the physical world and from the phonema dealt with by phycology.

Social Facts are ideas in the “collective mind” of a society.

The collective nind of a sociedty is something that exist over and above the individual members of society, and it`s ideas are only indirectly and imperfectly reflected in the mind of people who make up that society.

The legal system of a society is a relatively salient example of a highly structured social facts which has effects, often very tangible ones, on the lives of all the members of the society.

The concrete data of parole are produced by individual speakers, but language is not complete in any speaker; it exist perfectly only within a collectivity.

Durkheim made some remarkable sociological discoveries, notably in his work on Suicide.

|

Tarde stressed that sociological generalization how only because individual human beings have a propensitive to imitate one another.

The dialigue between Durkheim and Tarde was carried on in the journals over a number of years, with consederable passion on both sides: it culminate in a public debate between the two men at the Ècole Practique des Hautes Ètudes in Paris in December 1903.

|

Chomsky himself actually identifies his notion of linguistic competences with Saussure language.

Chomsky`s “competence”, as the name suggested, is an attribute of the individua, a phychological matter, he often defines competence as “the speaker-heare`s knowledge of his language.

Chomsky is American a that linguistic self-comfidence seems less common in American than in British society, perhaps because of the large proportion of Americans whose command of English is only a couple of generations old, both style the USA has not given itself the language-canonizing institution on France.

|

The philosopher Hilary Putnam has recently developed an argument which seems to show that the issue is more than a question of taste and that least one important aspect of language, namely semantic structure, most be regarded as a social rather than as a phychological fact.

Putnam`s argument is suble and elaborate, and it is not posible to do full justice to it within the scope of this book.

Argument is directed largely at linguistics of the contemporaly Chomskyan school, it is relevant to make a further point.

|

miércoles, 1 de febrero de 2012

Concepts

Linguistics: The field of linguistic, the scientific study of human natural language, is a growing and exciting area of study, with an important impact on fields as diverse as education, anthropology, sociology, language teaching, cognitive psychology, philosophy, computer science, among others. Linguistics is concerned with the nature of language and (linguistic) communication.

Semantics: Is the study of meaning. An understanding of semantics is essential to the study of language acquisition (how language users acquire a sense of meaning, as speakers and writers, listeners and readers) and of language change (how meanings alter over time). It is important for understanding language in social contexts, as these are likely to affect meaning, and for understanding varieties of English and effects of style. The study of semantics includes the study of how meaning is constructed, interpreted, clarified, obscured, illustrated, simplified, negotiated, contradicted and paraphrased.

Prescriptive linguistics: It is also called “prescriptivism”, is the act of taking the official models of a language, and treating them as sacred perfect representations of the language, and enforcing them on people. For example, correcting someone who uses the word “ain’t”, even if it’s used in an appropriately casual way.

Descriptive Linguistics: It is also called “descriptivism”, and is the study of language as it is spoken (and written). The study of the grammar, classification, and arrangement of the features of a language at a given time, without reference to the history of the language or comparison with other languages.

Ethnography: The study and systematic recording of human cultures; also: a descriptive work produced from such research. The practice of ethnography usually involves fieldwork in which the ethnographer lives among the population being studied. While trying to retain objectivity, the ethnographer lives an ordinary life among the people, working with informants who are particularly knowledgeable or well placed to collect information.

Ethnolinguistics: A study of the relations between linguistic and nonlinguistic cultural behavior. It means the study of language as an aspect or part of culture, especially the study of the influence of language on culture and of culture on language.

Sociolinguistics: It is the study of the relation between language and society--a branch of both linguistics and sociology. Sociolinguistics encompasses a broad range of concerns, including bilingualism, pidgin and creole languages, and other ways that language use is influenced by contact among people of different language communities (e.g., speakers of German, French, Italian, and Romansh in Switzerland). Sociolinguists also examine different dialects, accents, and levels of diction in light of social distinctions among people.

Generative grammar: Is a branch of theoretical linguistics that works to provide a set of rules that can accurately predict which combinations of words are able to make grammatically correct sentences. Generative grammar has been associated with several schools of linguistics, including transformational grammar, relational grammar, categorical grammar, and lexical-functional grammar. Generative grammar can be thought of as a way of formalizing the implicit rules a person seems to know when he or she is speaking in his or her native language.

Universal grammar: In linguistics, the theory of universal grammar holds that there are certain fundamental grammatical ideas which all humans possess, without having to learn them. Universal grammar acts as a way to explain how language acquisition works in humans, by showing the most basic rules that all languages have to follow.

The basic idea of universal grammar, that there are foundational rules in common among all humans, has been around since the 13th century.

Neurolinguistics: The study of the neurological mechanisms underlying the storage and processing of language. Although it has been fairly satisfactorily determined that the language centre is in the left hemisphere of the brain in right-handed people, controversy remains concerning whether individual aspects of language are correlated with different specialized areas of the brain.

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)